Case Report - (2024) Volume 9, Issue 1

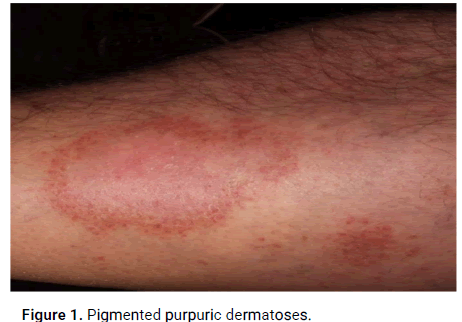

Pigmented purpuric eruptions are a group of benign cutaneous conditions usually recognized by their pinpoint petechiae and purpura on a brown, red, or yellow base. Pigmentary changes are typically found on the lower extremities, and occasionally on the trunk and upper extremities. The eruptions may present with pruritus, but are typically asymptomatic and chronic in nature. Here we present a case of capillaritis and a review of literature.

Pigmented purpuric eruptions • Petechiae and purpura • Capillaritis

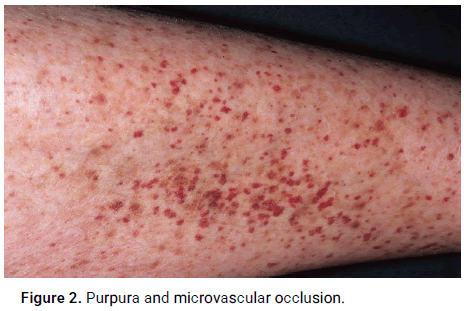

Pigmented purpuric eruptions are usually recognized by their pinpoint petechiae and purpura on a brown, red, or yellow base. The purpura is non-palpable, although there may be associated lichenification, scaling, and atrophy. Traditionally, there are 5 clinical entities that pigmented purpuras have been divided into: Schamberg’s disease, eczematoid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetankis, Majocchi’s disease, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, and Lichen aureus [1]. Histologically, the hallmark of all pigmented purpuras is capillaritis of the upper dermal vessels, characterized by perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate consisting of T cells, Langerhans cells, and macrophages, with extravasation of red blood cells and hemosiderin deposition. The epidermis is normal except in Schamberg’s disease where spongiosis may be seen, and Gougerot and Blum where there may be associated lichenoid changes. There is no evidence of vasculitis or fibroid necrosis histologically [2].

A previously healthy 35 year old Caucasian female with a 6 month history of bilateral lower extremity rash with itching that comes and goes presented to our clinic for initial dermatology consultation. The patient reported the rash had not spread since first presenting and denied any viral illness or bacterial infections preceding the rash. Patient denied fever, cough, vomiting, diarrhea, joint pain or swelling. She had been prescribed triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream by her primary care physician and reported improvement in itching but no improvement in appearance after use for 2 weeks. Of significance on exam, a nonpalpable petechial rash over the bilateral lower extremities. Remainder of the skin exam was within normal limits.

On dermoscopic exam, copper-red pigmentation was noted with red and brown dots. Patient was educated on capillaritis and informed to contact our office for re-evaluation if rash spreads, becomes more symptomatic, or if she develops any unusual symptoms. She was advised to continue triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream twice daily as needed for itching and to not use for more than 2 weeks per month [3].

Figure 1: Pigmented purpuric dermatoses.

Figure 2: Purpura and microvascular occlusion.

Pigmented purpuric eruptions are uncommon in pediatric patients, with the most commonly reported pigmented purpura in this age group being Schamberg’s disease. The etiology remains unknown; however, there are various proposed mechanisms about the pathogenesis of pigmented purpuric eruptions [4]. Capillary dilation and fragility is one mechanism that has been proposed as this may lead to rupture of the papillary dermis capillaries with possible aneurysmal dilation of the end capillaries. Other factors that have been reported to play a role are exercise, focal infections, venous hypertension, gravitational dependency, contact allergy to dyes and clothing, and chemical and drug ingestion [5]. Cell-mediated immunity has also been proposed in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpuras. In Schamberg’s disease it has been shown that perivascular infiltrate consists primarily of CD3+, CD4+ and CD1a+ dendritic cells (i.e., Langerhans cells), with close spatial contact between lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Upon analysis of adhesion molecules, it was found that infiltrating cells strongly expressed Leukocyte Function Associated-1 (LFA-1) antigen and ICAM-1, while endothelial cells expressed ICAM-1 and ELAM-1.

This suggests that adhesion molecules may play a role in lymphocyte trafficking to areas of inflammation and may regulate interactions between lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNFα) stimulated by ELAM-1 may lead to release of plasminogen activator inhibitor or defective release of endothelial plasminogen activator, which have also been observed in pigmented purpuric eruptions. As well, the role of Langerhans cells and helper T cells, in addition to HLA-DR expression on lesional keratinocytes believed to be characteristic of cytokine-mediated dermatosis, has been demonstrated. Further suggesting the role of immune complexes in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpuras is the deposition of C3 and C1q on the wall of lesional blood vessels [6].

Schamberg’s disease (progressive pigmentary purpura) was first described by Schamberg in 1901 in a 15-year-old boy as “diffuse, reddish-brown, non-elevated, irregular oval patches” with borders consisting of “pin head size, reddish-brown, scarcely elevated puncta or cayenne-pepper spots” which represent the extravasated red blood cells or hemosiderin deposits. More commonly described in males, this is a chronic disease with times of remission and exacerbation. It has been noted that the disease can fade after months or years and spontaneously remit in a subset of those affected. The lesions are typically limited to the lower extremities, most commonly on the bilateral tibial regions, but may be unilateral or involve the thighs, buttocks, trunk, and upper extremities [7]. Lesions may be asymptomatic; however mild pruritus may be an associated feature, especially during an exacerbation. Two cases of Schamberg’s disease have been reported affecting children as young a 1-years-old. Laboratory studies are normal and there are no other illnesses or physical abnormalities present in these patients. While the etiology remains unknown, there has been association of Schamberg’s disease with ingestion of medications such as acetaminophen, carbamols, meprobamate, thiamine, and aspirin. As well, an association with contact dermatitis to wool has been reported. Systemic steroids have been reported to clear the lesions; however, they are not warranted for use in children as this condition is benign. Currently there is no other treatment that has consistently proven to be of benefit in children. Modalities that have been attempted include topical steroids, ascorbic acid, antihistamines, griseofulvin, pentoxifylline, the antiallergic drug tranilast, and support stockings. Upon review of recent literature, a case of successful psoralen combined with ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatment has been described in a 10-year-old male and three cases of successful narrowband Ultraviolet B (UVB) therapy have been described in pediatric patients [8].

Eczematoid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis is described as a variant of Schamberg most commonly occurring in males that is generalized and pruritic. Lesions localize to the lower extremities and can rapidly spread to the trunk and upper extremities. Persistent scratching may lead to lichenification of the lesions. The lesions are typically chronic and may spontaneously remit after a few months; however, recurrences can occur. There has been one case reported of a 10-year-old male with eczematoid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis who was diagnosed two years after onset of the lesions. He was treated with narrowband UVB for two months and had clinical remission with no new lesions on a 7-month follow-up.

Majocchi’s disease (purpura annularis telangiectoides) was first described by Majocchi in 1896 as annular, purpuric lesions and punctate telangiectatic lesions on the lower extremity of a 21-yearold male. There is a higher prevalence of this disease in adolescent and younger adult females. The lesions are usually distributed in variable numbers symmetrically on the lower extremities, but may spread to the trunk and upper extremities. Typically asymptomatic, the lesions often present with central clearing and less frequently atrophy. Like other pigmented purpuric eruptions, the condition may be chronic and last for months to years with episodes of remission and exacerbation. Colchicine and 0.25%dichlorisone topical cream have been reported in two separate case reports as a treatment option for adolescents affected by this disease. A more recent case report shows successful treatment of a 13-year-old female with narrowband UVB, with no evidence of recurrence at follow-up one year later. However, there is currently no treatment that has consistently proven beneficial [9].

Pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum is extremely rare in children, mainly affecting older men ages 40 to 60-years-old. Lesions are typically rust-colored polygonal, flat-topped lichenoid papules that coalesce into plaques with erythema and scaling. The lower extremities are most commonly affected, but the trunk and upper extremities may also be involved. Patients usually are asymptomatic, but may report mild pruritus. It has been reported that lesions respond well to PUVA therapy.

Lichen aureus was first described by Marten in 1958 as “lichen purpuricus.” The lesions are typically golden to purplish lichenoid macules and papules that may clinically appear like a bruise. Lichen aureus is usually asymptomatic, but may be mildly pruritic, and commonly presents symmetrically on the lower extremities of young adults. Although, there have been documented cases of lichen aureus having truncal, upper extremity, and unilateral involvement. In addition, lesions may present in a segmental distribution, following the lines of Blaschko, dermatomal distribution, or follow the distribution of superficial or deep veins. Lichen aureus tends to be a chronic condition that may spontaneously resolve. The etiology remains unknown; however, lichen aureus has been associated with capillary fragility, immune complex-mediated and/or cell-mediated immune responses, venous insufficiency, infection, and drugs. There have been reported cases associated with trauma but its role in the pathogenesis of lichen aureus remains unclear. Topical steroids have not been particularly effective in treating lichen aureus, and there is no justification to treat children with systemic corticosteroids despite the fact they may be beneficial. Recent case reports have shown good response to PUVA, topical pimecrolimus, topical methylprednisolone, and combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin. However, because of the benign and asymptomatic nature of the disease no treatment is warranted in children.

Despite the distinct clinical presentation of pigmented purpuric eruptions, it is important to keep in mind other conditions that may present similarly. Conditions to include are fixed or other drug eruptions, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, trauma, and self-induced hematomas or “suction-cup” lesions. It is also important to know that early stages of Mycosis Fungoides (MF), a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, may present similarly to a pigmented purpuric eruption both clinically and histologically. There are three relations that have been well documented between MF and pigmented purpuras: MF can present clinically as pigmented purpuric eruptions; pigmented purpuric eruptions may precede MF and pigmented purpuric eruptions can stimulate MF histologically. Mycosis fungiodes is a rare disease in the pediatric population, but it should be considered in cases of pigmented purpuric eruptions that are persistent and progressive.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Velasquez RM, et al. "Pigmented Purpuric Eruptions: A Case Report". Dermatol Case Rep, 2024, 9(1), 1-3.

Received: 28-Jan-2020, Manuscript No. DMCR-24-3234; Editor assigned: 31-Jan-2020, Pre QC No. DMCR-24-3234 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Feb-2020, QC No. DMCR-24-3234; Revised: 15-May-2024, Manuscript No. DMCR-24-3234 (R); Published: 12-Jun-2024, DOI: 10.37532/2684-124X.24.9.1.005

Copyright: © 2023 Velasquez RM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.