Review Article - (2013) Volume 2, Issue 5

Genital piercing has become a “social reality” in our present day culture. Its practice is not limited by sexual

preference, gender, age or background. There are a variety of complications, acute and chronic, related to the piercing of both male and female genitalia that can affect the individual and his or her sexual partner. It is therefore imperative for healthcare practitioners to be aware of the various genital piercing practices, the types of jewelry used and the potential complications which may arise in order to appropriately counsel and manage those patients withcomplications relating to their genital piercings.

Keywords: Genital piercing, Body piercing, Complications, Penile piercing, Clitoral piercing

Genital piercing is not a new phenomenon, nor is it of western origin. There has been anthropological and literary evidence of genital piercing in cultures throughout different eras in history. “De Medicina”, the medical treatise by Aulus Cornelius Celsus during the 1st century BCE is considered to be the best surviving text on Alexandrine medicine and describes male genital piercing techniques in detail [1]. “The Kama Sutra,” believed to have been written by the Sanskrit scholar, Vatsyayana, between 100-600AD makes reference to penile piercing in the second chapter [2]. In ancient Mayan civilization, there is evidence of royalty piercing their genitals as part of religious ceremonies as early as 700AD [2,3]. The Victorian era had Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, who allegedly wore a penile ring to secure his genitals to the right or left leg of the extremely tight pants he wore, as was the fashion of that period. Currently, the “Prince Albert” is reported to be the most popular style of penile ring [2,4-6].

In more contemporary societies, there is evidence of women with labial piercings in post-World War II Germany [2]. In the United States (US), body piercing was popularized within the past fifty years by Fakir Musafar, who through his Modern Primitive movement, established it as “body art,” promoting the use of “piercing, implants, tattooing, and branding as they were used in primitive societies to experience visual, emotional, and sensual expressions of the body that life would not normally provide” [7].

While genital piercing is not a new phenomenon, it has only started appearing in the US health care literature in the mid-1990s. Very little has been published on genital piercing, and prevalence rates remain elusive [6]. The trend of obtaining genital piercings for aesthetic and sexual reasons continues to increase and is not limited by age, gender, socioeconomical background, or sexual preferences. It has become a “social reality” of our present day culture, and physicians may be requested to place genital piercings by their patients or to treat complications. Therefore, healthcare practitioners should be aware of these practices, the type of jewelry that is used, the available research in this area and the possible complications that can arise. Additionally, healthcare practitioners should also be able to elicit an appropriate sexual history, provide counseling and competently manage complications and side effects of genital piercings [2].

Currently, when complications arise with their genital piercings, men and women are more likely to seek nonmedical advice from the Internet or a piercer rather than a trained healthcare provider. This is in part due to lack of confidence in clinician knowledge regarding piercings and fear of being told to immediately remove the piercing when this may not be necessary [5,6]. These apprehensions place men and women at a higher risk for delays in receiving appropriate medical care for piercing-related complications [4].

Body piercing is a largely unregulated industry in the United States [8]. Existing legislation varies considerably by state, as there is no federal mandate regulating body art [5]. Piercers are generally unlicensed, and many of the techniques are self-taught or learned as “hands on” apprenticeships [9]. The Association of Professional Piercers (APP) has a health, safety, and education web page that can be accessed at: https:// www.safepiercing.org. This resource provides information and links to sites addressing anatomy, infection control, and governmental sites related to health and safety, disease prevention, and health and human services [7]. Piercing of the female genitalia remains controversial as the WHO has defined four types of female genital mutilation (FGM): Type IV includes ‘pricking, piercing or incising of the clitoris and/or labia’, therefore it is argued that a person performing female genital piercing could be guilty of Type IV FGM even though the services are sought out and requested by the woman [2]. Despite these considerations, many women still have their genitals pierced.

While lay literature generally portrays genital piercings as a source of sexual pleasure and aesthetic satisfaction for those who possess them, medical publications have historically painted discriminatory pictures of genitally pierced persons. Despite supporting evidence, those with body piercings, in particular genital piercings, have at various times been labeled as “born criminal,” [6,10] more prone to have sexually transmitted infections (STIs), [6,11] and as sadomasochistic [6,12,13]. However, these labels have been largely based on postulated theories and preconceived assumptions. In a study by Willmott in 2001, a cohort of women with various body piercings who presented at an STI clinic were compared to non-pierced women at the same facility, and no relationship was found between piercing status and socio-economic status, method of contraception, multiple partners, or presence of genital infection [14].

In the more recent medical literature, studies have been published that corroborate the assertion of the lay literature, reporting that persons with genital piercings find them to be a source of sexual pleasure. Furthermore, these studies demonstrate that genitally pierced individuals do not generally fall into demographic subsets of criminals or fetishists as has been previously assumed. The majority of respondents of four surveys published in medical or nursing journals were college-educated and gainfully employed. They sought genital piercings to enhance sexual expression and improve sexual pleasure and reported that these desires were achieved following piercing [4,6,15,16]. Two surveys asked about sexual practices and drug use and both found that the majority of respondents were in monogamous relationships, had never been diagnosed with an STI, and reported no drug use [4,15].

Another survey, conducted by Body Art magazine and referenced in the British Medical Journal, revealed that among pierced respondents, 58% were married and less than 20% considered themselves to be sadomasochistic, fetishist, or exhibitionist [17,18]. The respondents with genital piercings reported being pierced for aesthetic and sexual pleasure purposes. In addition, a case study published in Obstetrics and Gynecology documented the enhancement of sexual pleasure following genital piercing. In the study, a previously anorgasmic woman was able to achieve daily orgasm following clitoral piercing [9].

There are three main types of jewelry used for genital piercing: the barbell, which is a straight bar with a ball threaded onto one of the ends that unscrews (also called a banana bar); the curved barbell; and the captive ring, an open ring in which a ball is inserted between two small dimples. It is removed by placing the tip of fine pliers in the ring and opened, which will cause the ball to fall out [7]. Medical professionals should be familiar with how these piercings can be removed. In the setting of the operating room, a piercing left in place on the surgical site when prepped does not guarantee complete sterility as part of the piercing remains within the tissue. Additionally, an unprotected metal piercing may ground the patient and cause a second-degree burn during electrocauterisation [3,7].

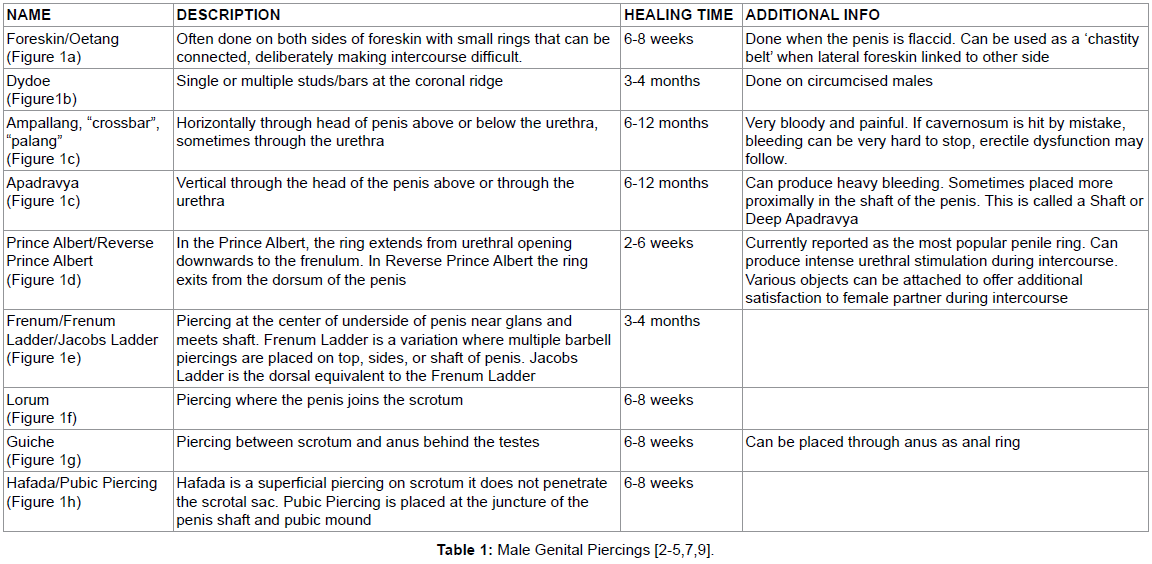

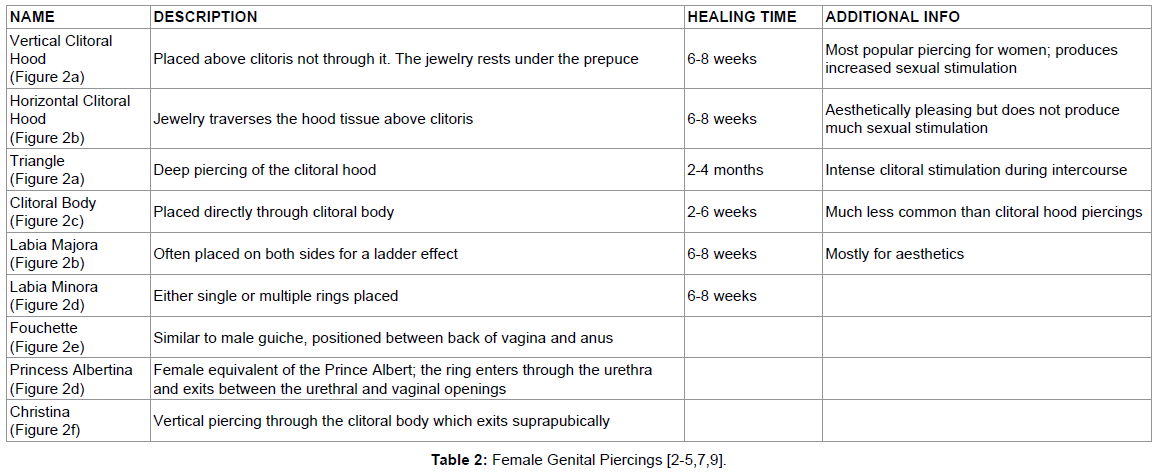

In regards to the types of genital piercing, they are numerous. Some of the most popular are listed in Tables 1 and 2 [2-5,7,9] and can be seen in Figures 1 and 2.

Complications of genital piercing are numerous and quite common. In a study of 445 men with genital piercings, 53% reported having at least one complication post procedure [4]. Another study that surveyed 84 men and women with genital piercings found that 52% reported at least one health-related problem following their piercings [6]. These complications may be related to the piercing process itself, or the persistence of a foreign body in the tissue [19-21]. In general, complications of genital piercings can be broadly divided into three categories: structural, infectious, and partner related.

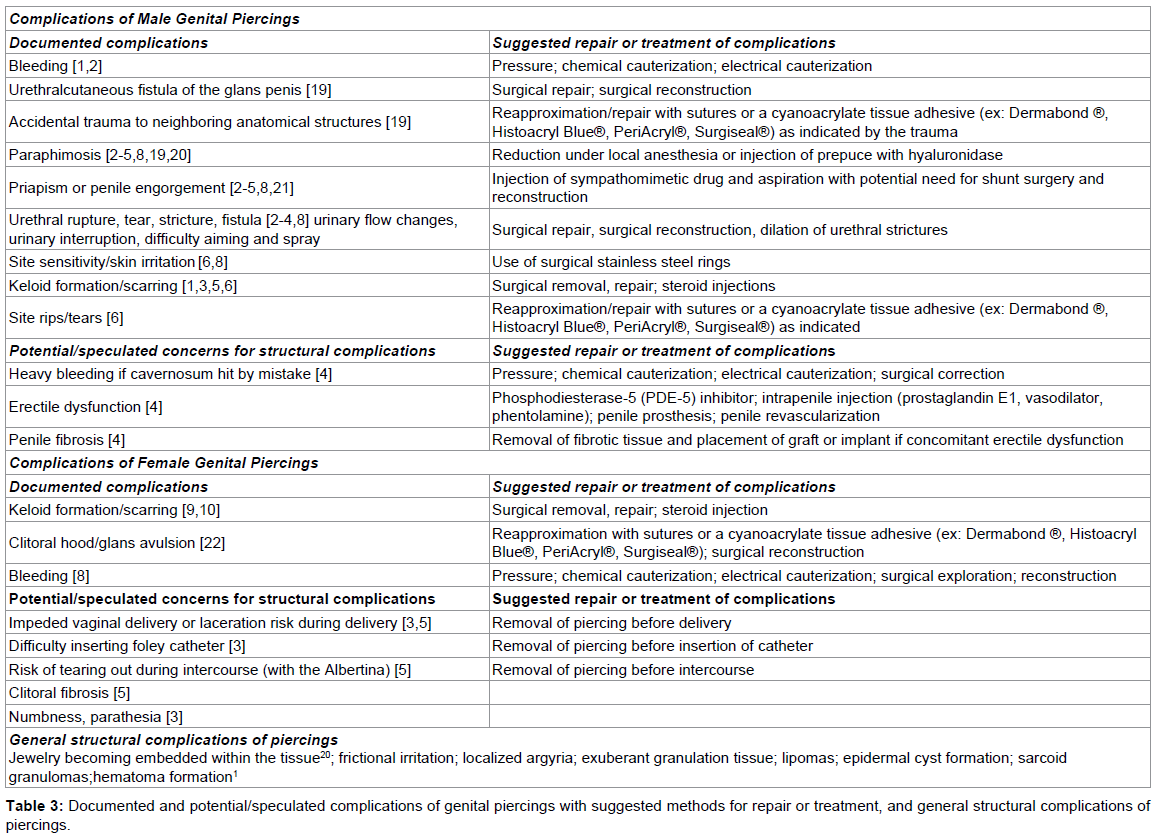

As described in Table 3, structural complications can be vast and vary by gender. Most of these complications relate to anatomical trauma and are either acute, such as bleeding, or chronic, such as scar/ keloid formation.

In males, bleeding is the major acute injury after piercing. Injury to the corpora cavernosa can cause significant bleeding. In the tip of the penis, a shunt between the corpora cavernosa and spongiosum/glans may be caused by a misplaced piercing and thus lead to significant bleeding acutely and later erectile dysfunction due to the inability of blood to accumulate in the corpora cavernosa. The urethra is vulnerable to fistula formation and/or stricture disease secondary to the presence of the piercing or after removal of the piercing. This may be due to acute injury and inflammation, chronic irritation, or poor healing properties, i.e. keloid or granuloma formation. In uncircumcised patients, paraphimosis may occur if the patient or piercer does not return the foreskin to the natural position covering the penile glans. As is shown in Table 3, treatment of structural complications related to genital piercing are specific to the injury. Piercings resulting in site trauma or tear can require surgical repair, while others, such as priapism, can be treated medically if the patient seeks care early enough. For piercings that damage the urethra, the severity of the urethral disease determines if the patient will require reconstructive surgery to correct the injury

In females, there are some areas of overlap, such as in the potential for bleeding, keloid or scar formation, stricture, and avulsion at the piercing site. Despite these similarities, the number and variety of documented structural complications are notably fewer in women compared to men. As in men, damage to the tissue at or around the piercing site may require surgical correction (Table 3).

Some individuals, such as those who are immune compromised, have multiple risk factors or an increased vulnerability for acquiring infectious diseases, making it difficult to ascertain whether transmission of the infection was caused by the genital piercing, or a pre-existing condition [2,8].

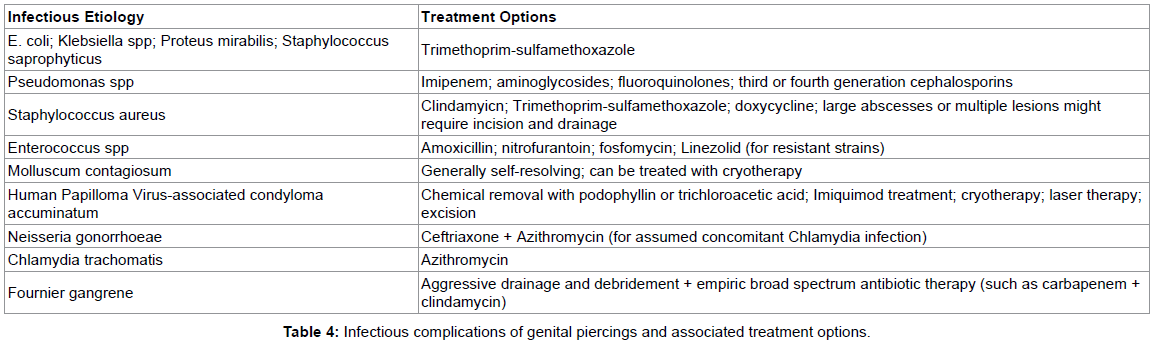

Risk of infection is not limited to genital piercing and can be associated with all forms of body piercing. Transmission of Hepatitis B, C, D and G has been reported, with some rare cases progressing to fatal fulminant hepatitis [22,23]. The possibility of transmitting HIV exists, and there have been cases reported of transmission of tetanus, leprosy, and tuberculosis after body piercings [8]. Bacterial infections with Staphylococcus aureus, Group A Streptococcus and Pseudomonas spp. are the most common following piercing. Most infections caused by body piercing are mild, localized and easily treated with topical antibacterial ointment, frequent cleansing and warm compresses with no need to remove the piercing [5,19]. However, the risk of cellulitis, carbuncles, impetigo, abscesses, post –streptococcal glomerulonephritis, endocarditis, as well as bacteremia and toxic shock syndrome still remains [1-3,19,20].

The most common causative agents of infections caused by genital piercing are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas spp, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus spp, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus [3]. While there have not been major studies, case reports, descriptive studies, and self-reporting surveys have described genital piercing-associated sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [24]. The data that have been collected challenge the assumption that individuals with genital piercings have an increased incidence of STIs [4,6]. However, an association between genital piercing and molluscum contagiosum has been reported, as well as an association between genital piercing and recurrent condyloma accuminatum caused by Human Papilloma Virus [2,6,19,20]. Penile edema (suspected to be caused by N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis ), prostatitis, testicular infection, and Fournier’s gangrene have all been reported in association with genital piercing, and squamous cell carcinoma has been diagnosed at the site of a Prince Albert’s ring piercing [3,5,25]. The mechanisms postulated as modes of transmission include trauma, chafing, and/or fistulas, caused by genital piercings allowing local invasion of microorganisms [24]. Genital piercings have also been noted to cause urinary tract infections [1]. Infectious complications of genital piercings can generally be treated with antibiotics (Table 4) with the possibility of incision and drainage for larger abscesses or cryotherapy for condyloma accuminatum.

Complications of genital piercings as pertaining to the sexual partner include condoms being damaged by protruding jewelry during intercourse, swallowed piercings causing choking and aspiration, trapping of piercings between the partner’s teeth, teeth-chipping, postcoital bleeding, and loss of jewelry [2,5,8,19,20].

While genital piercing is not a new phenomenon, it appears to be an increasingly common trend. Healthcare providers need to be aware of this practice as well as its complications and recognize the importance of conducting a thorough sexual history so that appropriate counseling and treatment can be offered. Medical documentation of genital piercings and their complications will provide data for further investigation.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.