Hypothesis - (2023) Volume 12, Issue 1

This study used a paired t-test to evaluate if after completing Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) training professional counselors felt that they have the ability to

• Teach techniques to parents targeting positive discipline,

• Teach techniques to children to learn new communication skills,

• Teach techniques to parents regarding strengthening their relationship with their children,

• Teach techniques that instill confidence in parents regarding child discipline,

• Teach techniques for parents to appropriately assess their child’s behavior and compliance. The result of this study may add to the body of knowledge for professional counselors who work with women and children in homes where domestic violence and IPV occur by providing professional counselors with a method of how to address the needs of the woman and child when they reside in a home where domestic violence or IPV is taking place.

Child abuse (CA) • Domestic violence (DV) • IPV • Professional counselors (PC) • Recidivism

Research on domestic violence or Interpersonal Violence (IPV) revealed that prevention programs do not address the needs of children living in an abusive household and professional counselors do not feel they have adequate training in both domestic violence and working with children to be effective in treating the needs of the woman in the abusive relationship and the needs of the child who is lives in the home where the abusive relationship is taking place [1, 2]. To fill this gap and show through evidence-based practice psychological programs, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) was selected.

PCIT is comprised of Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) and ParentDirected Interaction (PDI). CDI “resembles traditional play therapy and focuses on strengthening the parent-child bond, increasing positive parenting, and improving child social skills” [3]. During CDI, “the child guides the direction of play and makes autonomous decisions, not the parent. During CDI, Parents are reminded not to give commands, ask questions, or criticize the child; instead, they are prompted to praise, imitate, and reflect on the child’s actions”.

PDI “resembles clinical behavior therapy and focuses on improving parents’ expectations, the ability to set limits, and fairness in discipline and reducing child non-compliance and other negative behavior”. To lead the play session, parents learn to provide their children with effective, developmentally appropriate directions for appropriate and inappropriate behavior.

Batzer argued that women who complete PCIT programs are less likely to return to their previous behavior as “PCIT reduced the recidivism rates of maltreating families as compared to other treatment conditions” [4].

Whereas professional counselors reported in past research that having this additional tool provided them with an additional resource to assist clients who are in domestic violence and IPV relationships. Counselors also reported in past research that through the interactive training taught in PCIT that they could provide insight to the parent on how their actions towards their child were invoking their child’s reactions.

Findings in the research revealed that domestic violence and child abuse are considered two different issues in support organizations and psychological training in degree programs. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), domestic violence is defined as “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner (i.e., spouse, boyfriend/ girlfriend, dating partner, or ongoing sexual partner)” [5]. Whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) makes the argument that IPV is “one of the most common forms of violence against women and includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and controlling behaviors by an intimate partner”. Pain has extended the arguments of the CDC and the WHO, arguing that for “controlling behavior”. To be effective in a woman, there must be a form of psychological abuse and manipulation to instigate psychological control. Psychological control was found in research and argued by to consist of reprogramming a person to think what is occurring is normal. Gregory argued that reprogramming a person to think what others would consider abnormal is done by manipulating a person’s fears. Little and Pain, argued that once the perpetrator of domestic violence and IPV have gained the trust of the woman, then they use manipulative psychological tactics to get the woman to do what they want, which is controlling the woman’s physical and psychological behavior. Research also showed that psychological manipulation was no longer effective in getting the woman to do what the perpetrator of domestic violence and IPV wanted, the perpetrators of domestic violence and IPV used physical violence to control the woman. Hassanian-Moghaddam, along with Krahe, argued that through the use of physical abuse, women were rendered helpless and succumbed to learned helplessness. Learned helplessness is a psychological acceptance that occurs when a person who has been repeatedly exposed to acts of violence, threats, threats of violence, and humiliation stops trying to seek help, remove themselves from the situation, or both.

Research revealed that the psychological effects of being repeatedly exposed to domestic violence resulted in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), insomnia, anxiety, paranoia, depression, intestinal disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, frequent thoughts of suicide, and suicide attempts [6]. Hardy and Brown-Rice further argued that prolonged exposure to domestic violence resulted in “promiscuity, communal deterioration, and cardiovascular disease”.

Whereas repeated exposure to IPV has been linked to neurological and central nervous system changes in IPV victims known as “anoxic brain injury” because oxygen to the brain is cut off for extended periods. Campbell argued that changes in the neurological and central nervous system occur in women who have been repeatedly exposed to IPV due to repeated hits to the head of a person and cutting off their airways “Anoxic brain injury” consists of several forms of severity and has been shown to contribute to problems with concentration, attention, coordination and short-term memory, which may be relatively subtle to begin with. There may be headaches, light-headedness, dizziness, an increase in breathing rate, and sweating. There can be a restriction in the field of vision, a sensation of numbness or tingling, and feelings of euphoria. As the degree of anoxia becomes more pronounced, confusion, agitation or drowsiness appear, along with cyanosis - a bluish tinge to the skin, reflecting the lowered oxygen content of the blood, often most apparent around the lips, mouth, and fingertips. There may be brief jerks of the limbs (myoclonus) and seizures, both resulting from the damaging effects of lack of oxygen on the brain. If the anoxia is severe, it will result in loss of consciousness and coma.

Additional studies showed that the changes in the central nervous system have been linked to different dementias and cognitive impairments.

In 2020, the CDC reported that an estimated “5.3 million women”, “18 years or older” were victims of domestic violence. Of the “5.3 million women”, “2 million women sustained injuries that were reported, 145,000 of the women’s injuries required hospitalization, and 1,300 women died from the injuries they sustained from domestic violence”.

Child Abuse

Child abuse and neglect are serious public health problems and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been shown in research to have life-long impacts on a person’s physical and mental health [7]. According to the CDC, 1 in 7 children will experience some form of child abuse in their lifetime, and “1,770 children died of abuse and neglect in the United States”. The CDC classifies child abuse into four forms; physical, sexual, emotional, and neglect and is estimated to cost “428 billion dollars, which is equivalent to the combined cost of diabetes and stroke treatment and prevention programs in the United States.

Multiple authors argued that the adverse effects of child abuse for children who did not receive therapy to work through the psychological effects of being abused were children who were prone to abuse sex, and drugs [8, 9]. And were violent toward their classmates and friends. Children who were abused were also shown to have mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, As adults, children who were abused as children and did not receive therapy were shown to abuse their children and entered into abusive relationships [10].

The effect of domestic violence on children in homes where domestic violence is present

Authors argued that living in an environment where repeated and continuous physical, psychological, and emotional abuse are occurring on a regular or continuous basis can cause psychological damage to a child because as the abuse continues to occur in the home, the child comes to accept the physical, psychological, and emotional abuse as a normal way of living. McLeod and Loxton further argued that being exposed to domestic violence and IPV continuously impacts children throughout their lives as children who were exposed to domestic violence and IPV were shown to seek out relationships that mimicked what they viewed at home [11, 12]. Research showed that boys who were exposed to domestic violence and IPV mimicked the behavior that they saw their fathers display against their mothers. This included calling women foul and derogatory names and using physical violence to make a woman submit to what they wanted the woman to do. Whereas women were shown to mimic the behavior they saw their mothers display when they were being abused and how their mothers acted after they were abused. Examples cited in the research were women who were timid and succumbed to what their boyfriends wanted, which included sex when they were not ready [13]. Girls who were exposed to domestic violence and IPV continuously were also shown to rationalize their boyfriend's behavior.

The examples found in the research are consistent with arguments made by those who argued that parental influence has the strongest influence on social learning for children because children look to their parents for guidance and advice. Tasi further argued that children who have grown up in homes where repeated abuse occurs and enter into a relationship that is opposite to what the child viewed growing up, will do things to “normalize the relationship” so the relationship mimics what the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse saw growing up [14]. Examples cited in past research were, “cheating, lying, and stealing” argued that “cheating, lying and stealing” is inadvertently sabotaging the good in the relationship because growing up the child who was exposed to repeated physical and psychological abuse did not see good things occurring between their mothers and fathers. Monnant and Chandler further argued that men and women who enter into a relationship with a man or woman who has been exposed to repeated physical and psychological abuse as a child will eventually leave the relationship because they do not understand why the man or woman is acting and reacting the way he or she is argued that after a mate has left the relationship with someone who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child, the man or woman who was exposed to the repeated abuse will either blame him or herself for the failed relationship or convince themselves that the person’s intentions were false from the beginning [15]. Research further argued that in an attempt to regain what the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child views as normal, the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child will enter into a relationship with a person who mimics the behavior that the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child saw growing up thereby repeating the cycle of abuse.

The need for this study became apparent after an extensive literature review of psychological therapies revealed that the separation designated in support organizations and psychological training programs revealed that multiple professional counselors lack the abilities and training to address the needs of women and children who are residing in homes where domestic violence is taking place. Additionally, because of the inability of how to address the needs of women and children residing in homes where domestic violence is taking place concurrently, professional counselors will address the need of the parent or the child and then refer the other to another psychologist who specializes in the area [16]. The inability to address the needs of women and children who are residing in homes where domestic violence is taking place. with one professional counselor has detoured women and children from seeking psychological counseling and resulting in “53% of women and children remaining in abusive households every year”.

This study proved promising in meeting the needs of women and children residing in domestic violence homes by providing professional counselors with an evidence-based training program that addresses the needs of women and children [17, 18].

Available knowledge

An in-depth detailed search was conducted on the Internet online library databases for scholarly peer-reviewed articles on the subject. Through the use of ProQuest, EBSCO Host databases, along with Google Scholar, articles regarding the physical, psychological, and sociological, effects of prolonged exposure to domestic violence and IPV, along with the after-effects of domestic violence and IPV for women were located. Google Scholar was used to find information regarding Evidence-based Practice Cognitive Behavioral Therapies Interventions that addressed domestic violence, IPV, and child abuse prevention within the theory.

The search terms utilized were; domestic violence, interpersonal violence, IPV, IPV in urban areas, IPV in rural areas, violence against women, patriarchal values, domestic violence after effects, escaping domestic violence, domestic violence survival stories, IPV after effect, escaping IPV, IPV survival stories, PTSD and domestic violence, PTSD and IPV, domestic violence prevention programs, interpersonal violence prevention programs, IPV prevention programs, domestic violence, and interpersonal violence prevention programs, child abuse, child abuse theories, child abuse prevention programs, domestic violence and child abuse, interpersonal violence, and child abuse, and EBP Cognitive Behavioral Therapies Intervention on child abuse prevention and domestic violence. Both qualitative and quantitative research was reviewed. The following sections present the literature reviewed under various subtopics and themes related to the study.

Domestic violence

Domestic violence is defined as “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner (i.e., spouse, boyfriend/girlfriend, dating partner, or ongoing sexual partner)”. Whereas the WHO makes the argument that IPV is “one of the most common forms of violence against women and includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and controlling behaviors by an intimate partner”.

Evidence shown in prior research revealed that domestic violence has evolved, and perpetrators of domestic violence have learned the specifics of domestic violence laws and used the loopholes in the laws to their advantage to render their victims helpless. Hearn, Rendering a victim helpless was shown in research to be a form of psychological control [19].

Psychological control

Psychological control was found in research and argued to consist of reprogramming a person to think what is occurring is normal argued that reprogramming a person to think what others would consider abnormal is done through- manipulating a person’s fears expanded arguments, by arguing that manipulating a person’s fear is done to create the sense that the person who is doing the manipulation is the person who should be trusted and that they are the one who will not hurt the woman in the relationship, all argued that once the perpetrator of domestic violence and IPV have gained the woman’s trust, then they use manipulative psychological tactics to get the woman to do what they want, which is controlling the woman’s physical and psychological behavior. Examples noted in the authors’ arguments were getting the woman to change her outward appearance and controlling who the woman did and did not talk to Burnette furthered arguments stating that psychological control is making the person believe that physical alteration is what the person should do to better themselves to be better towards the person committing the IPV argued that the other part of psychological control is the altering of the person’s thoughts and emotions so the only thing the person thinks about is pleasing the person committing the IPV and putting the person committing the IPV above all other things in their lives. Examples cited in studies were convincing women that they should not talk to their family or friends because they do not understand Women were also shown to be forced to give up things they loved or loved doing because they took time and attention away from the person committing the IPV.

Multiple authors argued when psychological manipulation was no longer effective in getting the woman to do what the perpetrator of domestic violence and IPV wanted, perpetrators of domestic violence and IPV used physical violence to control the woman. The purpose of using physical violence was to escalate the perpetrator of domestic violence and IPV’s physical and psychological control over the woman.

Psychological effects of escaping abuse

Wilson examined the after-effects of leaving an IPV relationship. In their study, Maori women described in detail the extremes they were willing to go to maintain their safety while they were in, during, and after leaving an IPV abusive relationship. Extremes noted in this study were changing their physical appearance because the person committing IPV stated they should and having sex when they did not want to because they did not want to be forced into having sex through physical intimidation. Participants in this study stated after they left the IPV relationship they did not feel safe going outside at night and would check, double-check, and re-check the locks on their doors and windows to ensure that they were locked. Participants also reported moving frequently so that the perpetrator of IPV could not find them. Salcioglu argued for a victim of IPV to deal with the physical abuse they were exposed to, they must acknowledge and deal with the psychological abuse they were exposed to. Salcioglu argued that the battle that goes on in an IPV victim’s head will continue until they do both.

IPV and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The psychological effects of being repeatedly exposed to domestic violence resulted in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), insomnia, anxiety, paranoia, depression, bowel disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, and frequent thoughts of suicide, and suicide attempts, further argued that prolonged exposure to domestic violence resulted in “promiscuity, communal deterioration, and cardiovascular disease”.

Whereas repeated exposure to IPV has been linked to neurological and central nervous system changes in IPV victims known as “anoxic brain injury because oxygen to the brain is cut off for extended periods, argued that the neurological and central nervous system changes occur in women who have been repeatedly exposed to IPV because of the repeated hits to a person's head and cutting off their airways “Anoxic brain injury” consists of several forms of severity and has been shown to contribute to problems with concentration, attention, coordination and short-term memory, which may be relatively subtle to begin with. There may be headaches, light-headedness, dizziness, an increase in breathing rate and sweating. There can be a restriction in the field of vision, a sensation of numbness or tingling and feelings of euphoria. As the degree of anoxia becomes more pronounced, confusion, agitation, or drowsiness appear, along with cyanosis - a bluish tinge to the skin, reflecting the lowered oxygen content of the blood, often most apparent around the lips, mouth, and fingertips. There may be brief jerks of the limbs (myoclonus) and seizures, both resulting from the damaging effects of lack of oxygen on the brain. If the anoxia is severe, it will result in loss of consciousness and coma. Additional research revealed that the changes in the central nervous system have been linked to different dementias and cognitive impairments.

Physical violence

Tactics utilized through threats of physical violence are not similar to psychological control because physical violence is instant, whereas psychological control occurs over time [20]. Additionally, with physical violence, the pain diminishes over time, whereas the memory of the physical abuse has been found to continue over time. Multiple authors argued that the tactics of using physical violence to control someone were similar to those found in bullying.

Bullying

Bullying is defined as “a form of aggressive behavior in which someone intentionally and repeatedly causes another person injury or discomfort. Bullying can take the form of physical contact, words, or more subtle actions” [21-23]. Studies showed that in IPV relationships the abuse starts with psychological manipulation, which catches the person off guard. Once the perpetrator can get away with the psychological manipulation, the perpetrator proceeds to psychologically control the victim through threats that consist of something the victim fears, such as losing something valuable, or the perpetrator leaving the relationship. Physical violence was shown to enter into the relationship when the person could no longer be emotionally manipulated.

Societal influence on abuse

For domestic violence and IPV to be accepted in society there has to be a physical and psychological acceptance of what is occurring to another human being is perceived as normal. Burnette argued when a segment of society makes their own rules and regulations for how a family should and should not operate and children are not exposed to anything other than what their parents and their society have taught them, the children come to accept their roles in society and the cycle of abuse continues.

Holtz argued that one of the reasons that a person remains in an abusive situation is because the person’s social environment has an impact on the person’s physical and mental well-being. The author argues that the reason the social environment can impact a person’s mental wellbeing is due to continued, repeated exposure to the environment [24]. Signorello furthered argument that when a person is continually exposed to a particular environment a person will modify their physical behavior in an attempt to physically control or modify the situation. This is known as the psychoanalytic theory of defense mechanism where people “deny or distort their reality in order to defend themselves against feelings of anxiety and unacceptable impulses” Ziegler, Gregory argued that women in domestic violence and IPV relationships repeatedly rationalize to themselves and others round them that the person committing the violence against them does not mean to do what they do to them.

Child abuse

“Child abuse and neglect are serious public health problems and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) that can have long-term impact on health and wellbeing”. According to the CDC, 1 in 7 children will experience some form of child abuse in their lifetime and “1,770 children died of abuse and neglect in the United States” . The CDC classifies child abuse into four forms; physical, sexual, emotional, and neglect and is estimated to cost “428 billion dollars”, which is equivalent to the combined cost of diabetes and stroke treatment and prevention programs in the United States.

Additionally, the adverse effects of child abuse for children who did not receive therapy to work through the psychological effects of being abused were children who were prone to abuse sex, drugs, and were violent towards their classmates and Children who were abused were also shown to have mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, As adults, children who were abused as children and did not receive therapy were shown to abuse their children and entered into abusive relationships.

The effect of domestic violence on children in homes where domestic violence is present

Ward, Theule, and Cheung, argued that living in an environment where repeated and continuous physical, psychological, and emotional abuse are occurring on a regular or continuous basis can cause psychological damage to a child because as the abuse continues to occur in the home, the child comes to accept the physical, psychological, and emotional abuse as a normal way of living [25]. McLeod further argued that being exposed to domestic violence and IPV continuously impacts children throughout their lives as children who were exposed to domestic violence and IPV were shown to seek out relationships that mimicked what they viewed at home. Research showed that boys who were exposed to domestic violence and IPV mimicked the behavior that they saw their fathers display against their mothers. This included calling women foul and derogatory names and using physical violence to make a woman submit to what they wanted the woman to do. Whereas women were shown to mimic the behavior they saw their mothers display when they were being abused and how their mothers acted after they were abused. Examples cited in studies were women who were timid and succumbed to what their boyfriends wanted, which included sex when they were not ready. Girls who were exposed to domestic violence and IPV continuously were also shown to rationalize why their boyfriends acted and reacted the way they did. Examples cited in research were, “it is my fault”, “I did not do what he asked”, “I am not pretty enough”, and “he does not mean it when he acts this way”.

The examples found in past research are consistent with arguments made by Tasi who argued that parental influence has the strongest influence on social learning for children because children look to their parents for guidance and advice. Tasi further argued that children who have grown up in homes where repeated abuse occurs enter into a relationship that is opposite to what the child viewed growing up, the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse will do things to “normalize the relationship” so the relationship mimics what the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse saw growing up. Examples cited in studies were, “cheating, lying, and stealing” argued that “cheating, lying and stealing” is inadvertently sabotaging the good in the relationship because growing up the child who was exposed to repeated physical and psychological abuse did not see good things occurring between their mothers and fathers, further argued that men and women who enter into a relationship with a man or woman who has been exposed to repeated physical and psychological abuse as a child will eventually leave the relationship because they do not understand why the man or woman is acting and reacting the way he or she is. Engel argued that after a mate has left the relationship with someone who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child, the man or woman who was exposed to the repeated abuse will either blame him or herself for the failed relationship or convince themselves that the person’s intentions were false from the beginning. Research further argued that in an attempt to regain what the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child views as normal, the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child will enter into a relationship with a person who mimics the behavior that the man or woman who was exposed to repeated abuse as a child saw growing up thereby repeating the cycle of abuse.

How victims of domestic violence transfer violence onto their kids

In studies examining the effects of living in domestic violence and IPV households on children, multiple authors argued that women who were subjected to repeated acts of domestic violence and IPV abused their children because the repeated acts of violence had changed how the woman learned to communicate her needs Chaffin argued that when women are exposed to repeated acts of physical, sexual, and psychological violence, a woman’s amygdala is changed. The amygdala is the part of a person’s brain that controls the fight or flight response. Research showed that people who are not exposed to repeated acts of violence will either fight or flee a situation and over time will recall how they acted and reacted if the situation presents itself again [26-30].

Whereas women who are exposed to repeated acts of physical, sexual, and psychological violence have reprogrammed their amygdala to survive moment to moment rather than situation to situation. Andruczyk argued that women who are exposed to repeated acts of physical, sexual, and psychological violence through domestic violence and IPV will recall how they acted and reacted in an abusive situation and what they did to survive the abusive situation. The same author made arguments in their research that this included how they disciplined their children to avoid being subjected to acts of abuse from their spouse or boyfriend.

Research also showed that parents who abuse their children were often victims of child abuse themselves Carter argued that when children grow up in abusive households, the repeated viewing and experiencing of abuse becomes what the child views as normal behavior [31]. Callaghan further argued that as the child matures into adulthood and has children of their own, the adult transfers the abusive behavior onto their children because the adult believes this is normal, acceptable child disciplining tactics [32].

The authors’ arguments are consistent with Bandura’s social learning theory, which makes the argument that people learn from one another, through “observation, imitation, and modeling”. Therefore, based on the arguments in Bandura’s social learning theory, to stop adult who were raised in IPV households and were abused as children from abusing their children, a positive form of “observation, imitation, and modeling” has to be introduced to the adult to change the adult who was abused as a child way of thinking towards physical, emotional, and sexual abuse [33].

Holtz further argued through Bandura’s social learning theory to change the person’s view on their environment and what they view as normal and not normal, a person has to be taken out of an environment where the abuse occurred to have time to process the new surroundings and view the environment as being different than the one they just left, further argued through Bandura’s social learning theory that repeated exposure to the new environment eventually becomes the person’s new normal.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is an EBP that was created to guide the psychologist's treatment of children with behavioral disorders. Numerous studies and authors have discussed PCIT’s effectiveness in treating children with Learning Behavior Disorder (LBD), Behavior Disorder (BD), Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) [34, 35]. Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). PCIT is comprised of Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) and Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI). CDI “resembles traditional play therapy and focuses on strengthening the parent-child bond, increasing positive parenting, and improving child social skills”. PDI “resembles clinical behavior therapy and focuses on improving parents’ expectations, ability to set limits, and fairness in discipline and reducing child noncompliance and other negative behavior”. The theoretical underpinnings of PCIT in CDI and PDI are attachment theory and Bandura’s social learning theory. Attachment theory states, that regardless of how a parent treats a child, a child forms a bond with their parents because children look to their parents for “guidance, reassurance, stability, food, shelter, and love” [36].

Whereas in Bandura’s social learning theory, the argument made is actions and reactions are a product of a person’s environment and to change how a person acts and reacts in a situation, the person has to be taken out of the environment. Once PCIT was being used to treat children with behavioral disorders, psychologists began to examine how the effects of a child’s environment influenced a child’s behavior. In studies examining the effects of children being exposed to a parent suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) young children were shown to “cower and hide”, when their parent was having a flashback to the PTSD moment. Whereas older children were shown to run away, join gangs, and abuse drugs and alcohol in attempts to deal with or their parents’ behavior. In studies examining child abuse, psychologists used PCIT to learn how the bond between a parent and a child is affected when the child is exposed to repeated abuse [37]. What psychologists found through PCIT was parents who abuse their children were often victims of child abuse themselves. In studies examining the effects of living in domestic violence and IPV households on children, through PCIT, psychologists discovered that women who were subjected to repeated acts of domestic violence and IPV abused their children because the repeated acts of violence had changed how the woman learned to communicate her needs Chaffin argued that when women are exposed to repeated acts of physical, sexual, and psychological violence, a woman’s amygdala is changed. The amygdala is the part of a person’s brain that controls the fight or flight response. The author further argued that people who are not exposed to repeated acts of violence will either fight or flee a situation and over time will recall how they acted and reacted if the situation presents itself again.

Arguments made in research surrounding PCIT claim that PCIT teaches parents specific techniques that can help a parent build a better relationship with their child, which were shown in research to include, “emotion regulation” and “improvement in children externalizing behaviors”. “Emotion regulation refers to the ability to use internal and external resources to monitor, maintain, and modulate the occurrence, duration, and intensity of emotional responses”. External behaviors were shown in research to be directed at the child’s physical environment and included, “aggression, along with lying, cheating, and stealing. Rostad argued that if parents do not learn to regulate their emotions when they discipline their child as the child ages, the child’s aggression will worsen, and the child will abuse drugs, alcohol, and sex [38]. The arguments made in favor of PCIT are; PCIT can help improve family dynamics by working to reduce negative behavior and interactions within the family and to practice new behaviors and ways of communicating that are more encouraging and reassuring. When practiced consistently, these new skills and techniques can instill more confidence, reduce anger and aggression, and encourage better individual and interactive behavior in both parent and child [39]. Research also acknowledges in this theory that a parent to a child is not limited to biological parents, but can also be applicable to foster parents, and immediate family members caring for children. Borelli argued that a theory needs to apply to more than one parent base because parental roles have changed from traditional theory methods that were used with children in earlier decades.

Counselor knowledge

Despite increasing research and resources devoted to reducing child abuse and neglect, rates in the United States remain stubbornly high. Medical professionals do not screen for domestic violence or IPV. The rationale provided was they did not feel qualified to make an assessment or know what questions to ask regarding domestic violence or IPV. “87% of doctors surveyed said they did not feel equipped to recognize domestic violence or IPV”. Additionally, “32% of the doctors that were surveyed stated that in instances where children were involved, their protocol was to notify social services”.

“28% of Emergency Room Doctors also reported feeling helpless” to help victims of domestic violence and IPV because they did not know whom to refer the woman to as shelters would open and close.

“58% of Psychologists reported while they have completed basic training for Domestic Violence, they do not feel qualified to work with women and children who are in Domestic Violence situations”. “15% of Psychologists reported that they do not know how to work with children who are being abused by their mother who is in a domestic violence situation”.

“35%” of Psychologists reported that women who are in domestic violence situations are more likely to complete a program where they participate in a program, rather than being talked to and told what to do by someone [40]. One participant stated I worked with a psychologist who showed me how to help myself”. By the end of the program, “I felt empowered”. This participant later reported that she was able to work through issues with panic attacks and when her child would be disrespectful.

Psychologists and psychiatrists were noted in several articles stating that the basics of working with people who “have experienced traumatic events” are covered. If you do not specialize in this specific area or “have training in this specific area”, you could overlook “important factors” [41]. One Psychologist was noted stating “I do not work with kids” [42]. I do not like it because I do not have the stomach to hear what they have been through. “There is something about hearing a child is being abused that gets to me”.

Rationale

The theoretical framework to be used in this study is Bandura’s social learning theory and attachment theory.

Bandura’s social learning theory

In 1963 Bandura’s social learning theory was created by Bandura and Walters to explain how behavior is learned through different social settings. According to Bandura, “pure behaviorism could not explain why learning can take place in the absence of external reinforcement. He felt that internal mental states must also have a role in learning and that observational learning involves much more than imitation” [43]. Three arguments made in Bandura’s social learning theory are;

• A person’s environment is influenced by their surroundings and the person’s reactions to their surroundings.

• A person’s reaction to their surroundings demonstrates a causeand-effect relationship, and

• A person learns by “observation and modeling”.

Person’s environment is influenced by their surroundings and the person’s reactions to their surroundings

Holtz made the argument that a person’s social environment impacts a person’s physical and psychological well-being because a person’s social environment is the physical environment that a person is exposed to daily. Signorello further argued that continuous exposure to a certain type of environment will cause people will adapt their physical lifestyle to their environment. Neal and Neal made the argument that when a physical environment does not project positive outcomes, a person will adapt to the negativity around them by partaking in the negativity. An example noted in the research was people living in poverty, where there were minimal jobs available. Research showed that people stopped trying to find work because their environment had shown them that looking for work was “futile “because nothing will ever change”.

Person’s reaction to their surroundings demonstrates a cause-and-effect relationship

McLeod argued that how a person acts and reacts within their environment has a direct correlation to the events that the person has been exposed to continually. An example cited in the literature was two boys who grew up in different neighborhoods but attended the same school. The first boy was able to understand the visuals provided in the algebra problem because the first boy had been exposed to the visuals that were depicted in the algebra problem in his neighborhood. Whereas the second boy was unable to relate to the visuals in the algebra problem because he had never been exposed to the visuals in the algebra problem in his neighborhood. However, when the teacher was able to relate the concepts depicted in the algebra problem to visuals that the second boy was exposed to in his neighborhood, the second boy was able to solve the algebra problem.

Bandura’s social learning theory proposes that a person learns by “observation and modeling”. Observation and modeling entail a person observing a particular behavior and then imitating the behavior [44-47]. McLeod argued that “there are specific steps in the process of modeling that must be followed if learning is to be successful. These steps include attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation”. Attention is what is paid to the behavior that is to be modeled. Deaton argued that modeling is more than copying behavior because, with copying, a person just acts the same way a person acts without attention to detail. An example cited in the literature was a co-worker who was disciplined by the manager for coming in late. Because of the disciplinary action the co-worker received, one employee reported leaving their house ten minutes early to avoid being late. The attention to time and discipline are rooted together in a co-worker’s mind that, if I do not leave early enough, I could be subjected to the same disciplinary action that my co-worker recently was.

Retention is remembering the actions and reactions within a certain situation and recalling the actions and reactions as a form of a “mental road map”. Chavis can be followed when the situation presents itself again. Bandura argued that retention comes from “internalizing information in our memories”. Chavis argued if the memory associated with the information that is stored is bad, a person will have a harder time recalling the information because people are taught not to think about bad memories and in some instances will block out a bad memory if the memory has a negative reaction associated with it. Whereas, if the memory has a positive experience with it, a person can recall the information needed much easier because the memory does not invoke negative feelings.

Reproduction of “previously learned information comes from “behavior, skills, and knowledge”. Behavior was cited in the literature as how a person acted and reacted in a situation, citing, if the person receives accolades for their behavior in a certain situation, the person is more likely to repeat the behavior. Whereas, if the person received negative feedback on their behavior, a person would seek out examples of behavior that were rewarded positively and study the behavior to learn the behavior and apply the behavior to a particular situation if the situation should arise again. Skills were noted in the literature as being derived from observing various social situations such as riding a bike, playing checkers, and walking a dog. Acquiring skills through friends was shown to be more sought out, rather than acquiring skills by observing a stranger because people place more trust in their friends rather than a stranger.

The motivation was shown to be influenced by the stimuli received in the behavior. As stated previously, if a person receives accolades for their behavior in a certain situation, the person is more likely to repeat the behavior. The motivation for the person is to continue to receive accolades. Whereas, if the person received negative feedback on their behavior, a person will not repeat the behavior, and the person will seek out examples of behavior that were rewarded positively and study the behavior to learn the behavior and apply the behavior to a particular situation if the situation should arise again.

Based on the arguments in Bandura’s social learning theory, people “can learn many things both good and bad, simply by watching each other”.

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory was created by John Bowlby in the 1950s. Dr. Bowley, a British Psychologist studied how and why that causes children to make an attachment to one parent. In his study, Bowley studied the reactions of infant children’s needs that were expressed through crying and their caregiver's response. Bowlby noted how the child over time would stop crying when the caregiver would enter the room, even if the child was not picked up. Bowley also noted how the cease of crying showed that the infant felt secure when the caregiver entered when they called out to them. In his study, Bowley argued, that “attachment is an emotional bond with another person”[48]. “Bowlby believed that the earliest bonds formed by children with their caregivers have a tremendous impact that continues throughout life.

The reverse argument was added to Bowlby’s 1950 argument in the 1970s by Dr. Mary Ainsworth which stated, that if a child does not bond with one of their caregivers, the lack of attachment continues into adolescence and adulthood affecting their relationships with others. Dr. Ainsworth noted how adults who did not form emotional or psychological bonds with one of their caregivers attempted to fill the void with material possessions resulting in excessive spending and unfulfilling sexual relationships.

Both the social learning theory and attachment theory are used in PCIT. PCIT is comprised of CDI and PDI. CDI “resembles traditional play therapy and focuses on strengthening the parent-child bond, increasing positive parenting, and improving child social skills”. This is consistent with the arguments made in Attachment Theory which states that children need to bond with one of their caregivers. Through “traditional play therapy”, children begin to rely on their parents as someone who will spend time with them. Over time, the child begins to rely on their parent for other things and begins to bond with the parent.

The teachings in PDI, which resemble clinical behavior therapy and focuses on improving parents’ expectations, ability to set limits, fairness in discipline, and reducing child noncompliance and other negative behavior, are consistent with social learning theory. This is because the child who has now formed a bond with their parent in CDI is looking to their parent for clear, consistent guidance on what is and is not acceptable behavior. Research showed children who grow up in homes where domestic violence is present do not have clear guidance on what is and is not acceptable behavior. Rather, the child like the parent has had their amygdala reprogrammed and is the surviving moment to moment. Through PDI, both the parent and the child are introduced to new forms of communication with each other. Over time, the new form of communication will become a regular form of communication. In PDI parents are taught to explain how and why to the child when addressing behavior, rather than saying don’t do that or stop it.

Operational definitions of study variables

The independent variable of this study was the EBP educational training provided to professional counselors to fill the gap in how to work with women and children who are living in homes where domestic violence is taking place. The independent variable is comprised of professional counselors’ abilities to teach techniques before and after the EBP training intervention. The dependent variables in this study are;

• Counselors' ability to teach techniques to parents targeting positive discipline,

• Counselors' ability to teach techniques to children to learn new communication skills,

• Counselors' ability to teach techniques to parents regarding strengthening their relationship with their children

• Counselors’ ability to teach techniques that instill confidence in parents regarding child discipline,

• Counselors’ ability to teach techniques for parents to appropriately assess their child’s behavior and compliance.

Study Assumptions

Assumptions in this study are, that all participants will be truthful in their responses. After participating in PCIT training, counselors will be able to apply the teaching techniques of CDI and PDI to women in domestic violence and IPV relationships. After participating in PCIT training,counselors will be able to address the needs of women in domestic violence and IPV relationships, along with the needs of the children who are living in households where domestic violence and IPV are taking place.

Specific Aims

The project aims to increase professional counselor knowledge of how to work with women and children who reside in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place. This was a quantitative study of professional counselor training as it related to the focus of preventing child abuse for children who live in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place.

To increase professional counselor knowledge of how to work with women and children who reside in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place, this capstone intervention promoted counselor training through PCIT that focused on working with women and children who reside in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place. Previous research surrounding PCIT use in domestic violence and IPV households where children are involved provided counselors with the ability to address the needs of the women and the child who resided in the home. Additional research revealed that counselors felt more confident when working with women in domestic violence relationships because they had a tool to reference that would provide them with the ability to show women how to get from point A to point B with their children, rather than just offering suggestions for “a leave plan”. Lloyd argued that women will stay in a domestic violent home rather than risk economic difficulty and homelessness for their children [49].

The purpose of this study was to investigate if the use PCIT increases the knowledge and skills of professional counselors and outreach counselors who work with women and children in domestic violence and IPV relationships. Additionally, this study may provide insight into preventing child abuse in homes where domestic violence and IPV are occurring, along with reducing the recidivism rates of women returning to their previous behavior and abusive households.

The author of this project targeted professional counselors who work with women and children residing in rural communities within the Midwest and Southeast where domestic violence and IPV are taking place. Research showed that domestic violence occurrences were high in these areas.

The outcomes of this project may join the body of knowledge concerning professional counselors and outreach counselors who work with women in domestic violence and IPV relationships. This research may also serve as the foundation for the future development of domestic violence, IPV, and child abuse prevention programs. This capstone aimed to increase professional counselors’ knowledge about using PCIT to work with women and children who are residing in domestic violent homes. The author of this capstone intervention promoted training education on how to use PCIT to professional counselors who work with women and children that reside in domestic violent homes. Previously, professional counselors had not been trained in this area.

In this training intervention, the recommendation of EBP, PCIT was used. During this study, the training intervention used for this project was comprised of two sections: general knowledge, and application. This training intervention was shown to be effective in improving professional counselors' knowledge about a therapy program that could be used to work with women and children who are residing in domestic violent homes. Statistical difference was shown in professional counselors’ knowledge at the end of the training intervention.

In this study, a probability sampling, a quantitative approach was utilized, where pretest and post-test responses were analyzed. According to Landrum, quantitative research involves examining relationships between variables and measuring quantities such as numbers on pre-and post-test scores and other measurements. In this study, a quantitative approach was used to explore professional counselors’ knowledge and abilities to work with women and children who are residing in domestic violent homes before and after the training intervention.

The minimum sample size to support the proposed statistical techniques was N=9. This research study included 9 professional counselors whose locations varied between the Midwest and the Southeast. The researcher investigated and gained insight into professional counselors’ attitudes toward using PCIT to work with women and children who reside in domestic violent homes.

The EBP training education intervention was given to the counselors for two, four-hour Saturday sessions that occurred on concurrent weekends of June 11, 2022, and June 18, 2022. After the last session was completed, the post-test was administered to gauge the knowledge that the participants had gained from the EBP training education intervention.

55% of the nine professional counselors in this study resided in the Southeast, and 45% resided in three different states within the Midwest. The professional counselors who resided in the Southeast ranged in age between 40 and 55. Whereas the professional counselors in the Midwest ranged in ages from 35-55. Educational levels varied between the Southeast and the Midwest professional counselors. In the Southeast, 50% had master’s degrees and 5% had PhD’s. Whereas in the Midwest, 15% of the professional counselors had master’s degrees and 85% of the professional counselors had PhD’s.

The training intervention used for this project addressed the exposition of CDI and PDI along with how to administer CDI and PDI to parents and children. Statistical difference was shown in professional counselors’ knowledge at the end of the EBP training intervention. The researcher prepared a PowerPoint for both CDI and PDI. In CDI training, the child is to lead the play and the parent is to follow the child’s lead and participate based on the child’s direction. The PowerPoint presentation that discussed CDI included steps and examples of how to guide parents through CDI. An interactive discussion session was conducted during the lecture, along with a question-and-answer session that followed the lecture.

n PDI training, the parent is taught how to instruct the child about the desired behavior outcome that they want to see from their child. In PDI training, parents are taught how to give consistent commands to their children through the PRIDE acronym. PRIDE stands for Praise, Reflect, Imitate, Describe, and Enjoy. The purpose of the PRIDE acronym is to provide a word that is easy for parents to remember and symbolic of the desired behavior outcome of the child. The researcher also prepared a PDF f ile that explained how to teach commands to parents using the PRIDE, acronym that provided a yes and no example so parents would have a reference of what they should and should not do. An interactive discussion session was conducted during the lecture, along with a question-andanswer session that followed the lecture.

Context

This study took place virtually through Zoom due to university restrictions that stated in-person studies must be conducted virtually due to COVID-19. Because of the restriction, participants were emailed a Zoom meeting request link. On the days and times of the meeting, participants logged into the Zoom meeting. According to the study, PCIT knowledge was affected by participants' knowledge of how to work with women and children living in homes where domestic violence is taking place.

The student researcher met with the counselor at Bates County Memorial Hospital in Southeastern Kentucky to discuss the study. Formal written permission from the research site was obtained. The counselor was eager to introduce the training project to the hospital. Also, the student researcher attended the staff meeting and presented the study, providing data on domestic violence, IPV, child abuse, and PCIT. The presentation of data was used to encourage and promote participation in this project. This project benefitted the organization by educating professional counselors on how to work with women and children together who are residing in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place.

In this study, professional counselors’ awareness and knowledge of PCIT and how to work with women and children together after the training was completed were shown.

Intervention

This study utilized a probability sampling, quantitative approach, where pretest and post-test responses were analyzed. According to Landrum quantitative research involves examining relationships between variables and measuring quantities such as numbers on pre- and post-test scores and other measurements. In this study, a quantitative approach was used to explore professional counselors' knowledge and ability to work with women and children who are residing in domestic violent homes before and after the EBP training intervention. The setting was virtual due to university restrictions that stated in-person studies must be conducted virtually due to COVID-19 restrictions. The intervention included interactive training for professional counselors on the administration and use of PCIT when working with women and children who are living in households where domestic violence is occurring. The inclusion criteria to participate in this study includes professional counselors who worked with

• A woman parent;

• Work with clients receiving psychological treatment for being in domestic violence or IPV relationship;

• Have one or more children that were exposed to the effects of the woman parent’s domestic violence or IPV relationship professional counselors were excluded from the study who do not work with;

• Women who are not currently receiving psychological treatment for being in domestic violence or IPV relationships; and

• Clients that have one or more children that were exposed to the effects of the woman parent’s domestic violence or IPV relationship.

• Domestic violence, IPV, and child abuse are significant public health issues.

Additionally, research has shown that professional counselors have limited knowledge of how to work with women and children who are residing in homes where domestic violence and IPV are occurring. Information regarding training therapies is essential to help professional counselors who work with women and children who are living in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place. Increasing professional counselors’ knowledge and awareness regarding preventive actions are acknowledged as a public health best practice. Thus, this study was conducted to determine the impact of educational training intervention on PCIT for professional counselors who work with women and children that are living in homes where domestic violence and IPV are taking place.

This study used the evidence-based education training intervention created by Dr. Sheila Eyberg known as PCIT. PCIT was created to guide the psychologist's treatment of children with behavioral disorders. PCIT is comprised of Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) and Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI). CDI “resembles traditional play therapy and focuses on strengthening the parent-child bond, increasing positive parenting, and improving child social skills. During CDI, “the child guides the direction of play and makes autonomous decisions, not the parent. During CDI, Parents are reminded not to give commands, ask questions, or criticize the child; instead, they are prompted to praise, imitate, and reflect on the child’s actions.

PDI “resembles clinical behavior therapy and focuses on improving parents’ expectations, ability to set limits, and fairness in discipline and reducing child noncompliance and other negative behavior”. To lead the play session, parents learn to provide their children with effective, developmentally appropriate directions. Parents are also prompted to reinforce their child’s desirable behavior and to discourage undesirable behavior by using consistent and suitable consequences”.

Research showed that PCIT can help improve family dynamics by working to reduce negative behavior and interactions within the family and practicing new behaviors and ways of communicating that are more encouraging and reassuring. When practiced consistently, these new skills and techniques can instill more confidence, reduce anger and aggression, and encourage better individual and interactive behavior in both parent and child.

Professional counselors were recruited via phone calls and email through web searches of public health officials, domestic violence shelters, and child abuse prevention centers in the Southeast and the Midwest. Participants who expressed interest in participating in the study were emailed a copy of a PowerPoint that discussed PCIT. Once the participants agreed to participate in the study, participants were issued computer-generated ID numbers and provided the Zoom link to login into the study. On the first day of the study, participants were issued the CDI questionnaire. Please see for a copy of the CDI questionnaire. The PCIT educational training began after the CDI questionnaire.

Participants were dismissed after 4 hours and returned the following Saturday morning to complete the PDI training and conclude the PCIT Training. At the end of the training, participants were re-issued the CDI questionnaire and the Evidence-based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). The EBPAS questionnaire is an evidence-based mental health provider's attitude toward the adoption of evidence-based practice. This learner’s role in the practice change was as an educator for professional counselors about the intervention in this project and as a resource for the hospital to support the practice change. Additionally, this learner was a doctoral leader during this project and collaborated with the hospital leaders to implement change in this organization. The team that participated in this project included professional counselors from the Southeast and the Midwest.

The CDI questionnaire and the EBPAS questionnaire were used to determine if the educational training intervention about PCIT was effective during this capstone study. Previously, at this organization, there was no education regarding PCIT given to professional counselors. The CDI questionnaire and the EBPAS questionnaire were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the study intervention. The CDI questionnaire consisted of 300 questions that dealt with child development and behavior. At the end of the PCIT training, counselors were directed on which questions they were to answer within the CDI questionnaire that addressed child behavior during development. Respondents’ responses were specific to questions that required either a yes or no response. The first pre and posttest were conducted by comparing the professional counselors' before and after-test responses. The second pre and post-test were conducted using the EBPAS questionnaire. The EBPAS consists of 8 questions that assess mental health provider attitudes toward the adoption of evidencebased practice. Respondents’ responses were to questions regarding their willingness to implement an EBP. Responses ranged from 0 to 4, with 0 being not at all and 4 being to a very great extent. The responses for CDI resulted in a possible score of 0-20 and 0-32 for EBPAS.

he CDI pretest was used to determine if the capstone intervention increased professional counselors' knowledge and awareness of PCIT. This evaluative method enabled the researcher to conclude if the educational training intervention was valid. When the post-test data was compared to the pretest data, a statistically significant improvement was evident. This study shows increased knowledge and awareness of an intervention method that professional counselors can use to work with women and children who reside in domestic violent homes. During this project, the proposed change in practice was to improve professional counselors’ knowledge of how to work with women and children who reside in domestic violent homes and reduce the recidivism rates of women returning to domestic violent homes and abusing their children.

In this project, a purposive sampling method was used, with a pre and post-intervention model to investigate a quantitative measure of professional counselors’ knowledge about PCIT. There was no evidencebased educational training in place to educate professional counselors on how to work with women and children who are living in domestic violent homes. The goal of the intervention was to provide professional counselors with a proven EBP method that could be used to work with women and children who reside in domestic violent homes.

This study intervention occurred during the semester break in between the spring and summer quarters of 2022, in June. The recruitment was open to professional counselors from March 1, 2022, to May 15, 2022. After the recruitment was completed, professional counselors completed two four-hour training education sessions conducted on June 11, 2022, and June 18, 2022. The nine participants all participated in the training education intervention sessions. The CDI questionnaire and the EBPAS questionnaire were issued pre and post-training to determine if the educational training intervention about PCIT was effective during this capstone study. Previously, at this organization, there was no education regarding PCIT given to professional counselors. The CDI questionnaire and the EBPAS questionnaire were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the study intervention. The CDI questionnaire consisted of 300 questions that dealt with child development and behavior. At the end of the PCIT training, counselors were directed on which questions they were to answer within the CDI questionnaire that addressed child behavior during development. Respondents’ responses were specific to questions that required either a yes or no response. The first pre and post-test were conducted by comparing the professional counselors' before and after-test responses to the CDI questionnaire.

The second pre and post-test were conducted using the EBPAS questionnaire. The EBPAS consists of 8 questions that assess a mental health provider's attitude toward the adoption of evidence-based practice.

Respondents’ responses were to questions regarding their willingness to implement an EBP. Responses ranged from 0 to 4, with 0 being not at all and 4 being to a very great extent. The responses for CDI resulted in a possible score of 0-20 and 0-32 for EBPAS. The intervention used in this study was PCIT education materials that consisted of multiple formats, including lectures, discussions, PowerPoint presentations, and YouTube videos, which were used during every 45 minutes to 60-minutes session. The educational training intervention used in this study was comprised of CDI, PDI, and PCIT. The posttest was conducted immediately following the second day of training using the CDI questionnaire and the EBPAS questionnaire. Collected data were coded and analyzed through a paired t-test.

Analysis

Data produced from the CDI questionnaire and the EBPAS questionnaire that was issued pre and post-training were analyzed using paired t-tests to provide evidence about the effectiveness of the capstone intervention. Quantitative methods were utilized to draw inferences from the data. Nine professional counselors that ranged in geographical locations from the Southeast to the Midwest participated in this PCIT education training intervention for 2 days. The PCIT education training intervention was comprised of three sections: CDI, PDI, and ( PCIT which were aimed at teaching professional counselors how to work with women and children who are living in homes where domestic violence is occurring.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention, a paired t-test analysis was performed from the answers to the confidence-based questions in the pre- and post-test. The mean score was calculated in the following sections

• Counselors ability to teach techniques to parents targeting positive discipline.

• Counselors ability to teach techniques to children to learn new communication skills.

• Counselors ability to teach techniques to parents regarding strengthening their relationship with their children.

• Counselors ability to teach techniques that instill confidence in parents regarding child discipline.

• Counselors ability to teach techniques for parents to appropriately assess their child’s behavior and compliance. Findings of the study pre and post-test are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean Difference and Standard Deviation CDI.

| CDU | Before PCIT Training |

|---|---|

| Mean | 22.11111111 |

| Variance | 52.61111111 |

| Observations | 9 |

| Pearson Correlation | 0.534469513 |

| Hypothesized Mean Difference | 0 |

| df | 8 |

| t Stat | -0.97022155 |

| P(T<=t) one-tail | 0.18 |

| t Critical one-tail | 1.859548038 |

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 0.36 |

| t Critical two-tail | 2.306004135 |

Findings show that the pre-intervention mean score for (M=22.1, S=7.25) after PCIT training (M=24.2, SD =6.11) conditions; t=8, p=2.30600413. A second paired t-test was conducted to measure professional counselors' feelings on using EBP methods to learn if the training program increased counselors' knowledge, skills, and competence before and at the end of the training. Findings of the pre and post-test are listed in table 2 Mean Difference and Standard Deviation shown through ECBI after PCIT Training (M=24.2, SD=3.27). Findings showed that professional counselors felt there was a significant increase in their knowledge, skills, and competence at the end of the training to use PCIT to work with women and children who are residing in domestic violence households.

Table 2. Mean difference and standard deviation ECBI.

| ECBI | Feelings Before PCIT Training |

|---|---|

| Mean | 12.77777778 |

| Variance | 17.69444444 |

| Observations | 9 |

| Pearson Correlation | 0.904644471 |

| Hypothesized Mean | |

| Difference | 0 |

| df | 8 |

| tstat | 603567451 |

| P(T<=t) one-tail | 0.073738511 |

| P(T<=t) two-tail | 0.147477022 |

| t Critical two-tail | 2.306004135 |

The findings in this study are consistent with past research that indicated through PCIT training programs, counselors have reported being better equipped to work with women and children who were in domestic violence relationships. Past research showed because professional counselors were unable to address the needs of women and children residing in homes where domestic violence is taking place concurrently, the professional counselors addressed the need of the parent or the child and then referred the other to another psychologist who specializes in the area. Research showed that the inability to address the needs of women and children who are residing in homes where domestic violence is taking place with one professional counselor has detoured women and children from seeking psychological counseling. Findings in the research showed that the inability to address the needs of the parent and the child residing in a domestic violent situation resulted in “53% of women and children remaining in abusive households every year” [50-53]. Findings in this study showed that this concern has been addressed through PCIT training because PCIT provides professional counselors with a tool they can reference that will show women how their actions and reactions are invoking their child’s behavior. Additionally, through PCIT, the bond between parents and children is strengthened. It is the ability to show parents how their actions are affecting their child’s behavior and the strengthening of the parental bond, through CDI and PDI exercises, which are components of PCIT that professional counselors can help women and children in a domestic violent home build a road map of how they will get from point A to point B, with point B being leaving the domestic violent home with their children and not returning to the domestic violent home once they have left.

Ethical Considerations

Because this study utilized paired t-tests to measure professional counselors’ confidence in feeling more equipped and knowledgeable to address the needs of a woman in a domestic violence relationship and the child who is living in the home where the abusive relationship is taking place after completing PCIT training, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) had to issue permission for the test to be conducted.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) is the governing body that oversees research involving human participants. The IRB’s express purpose is to ensure the rights and welfare of human participants in research are protected. Primary research is the collection of information or data directly from human participants such as in conducting surveys or obtaining personal participant information.

Human Study Protection Methods

Through the use of the Belmont Report, which forms the regulatory framework that governs ethical research involving human subjects obtaining informed consent, balancing risk and benefit, and selecting study participants appropriately will be utilized. The researcher was responsible for ensuring and obtaining the principle of informed consent, which ensures that the participants voluntarily decide to participate in the study and they understand the purpose, procedure, risks, and possible benefits of participation [54]. The researcher was responsible for ensuring that participants’ identities were not revealed. Participants in this study were identified by a computer-generated number. The researcher used a computer application to create computer-generated numbers. The researcher was responsible for confirming the study participant’s computer-generated number before the start of the study, during the administering of the CDI and PDI checklists, and after the study is completed and the participants complete the end of the study CDI checklists and the EBPAS questionnaire [55].

The participants selected for this study may benefit from the study f indings because the participants may have increased knowledge, skills, and competence in the use of EBP Parent-Child Intervention Therapy that can be used to effectively treat the needs of the woman in the abusive relationship and the child who is living in the home where the abusive relationship is taking place [56].

Bias

Bias in research must be acknowledged to ensure the validity of the test-finding results. Validity in quantitative research is established by ensuring that the tool or tools used in the study measure what they were intended to measure [57-61]. Additionally, in quantitative research, this is how confounding bias is mitigated. The data collection method used in this study was two EBP questionnaires that measure professional counselors’ knowledge before and after the training intervention. The researcher collected and entered the data.

Data produced from the paired t-test provided evidence about the effectiveness of the capstone intervention. A paired t-test analysis was performed from the answers to the confidence-based questions in the pre and post-test. The mean score was calculated in the following sections

• Counselors ability to teach techniques to parents targeting positive discipline,

• Counselors ability to teach techniques to children to learn new communication skills,

• Counselors ability to teach techniques to parents regarding strengthening their relationship with their children

• Counselors ability to teach techniques that instill confidence in parents regarding child discipline,

• Counselors ability to teach techniques for parents to appropriately assess their child’s behavior and compliance [57].

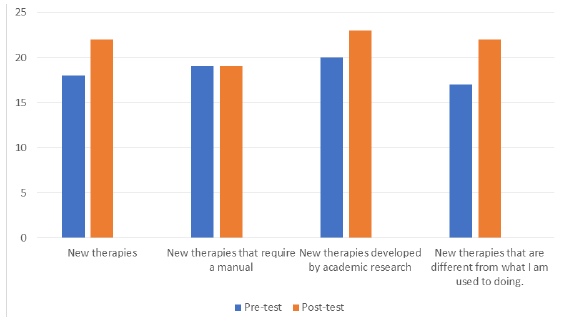

Findings of the study show that the pre-intervention mean score for (M=22.1, SD=7.25) after PCIT training (M= 24.2, SD=6.11 ) conditions; t=8, p= 2.30600413. Findings in the second paired t-test revealed professional counselors’ feelings toward implementing EBP interventions<00.5. Postintervention revealed that professional counselors were more inclined to use the intervention once the intervention was taught to them, Please see Figure 1 Implementing an EBP Prevention Program.

Figure 1: Implementing an EBP prevention program.

The findings from the EBPAS pre and post-test reinforce the findings from the pre and post-test for CDI and are consistent findings in research, which stated there is a separation designated in support organizations for psychological training programs to work with either women or children in domestic violence situations, but not both. Further evidence revealed that professional counselors would work with women and children in domestic violence settings if they had a program that had proven results and offered women and children who are living in domestic violent homes a plan of how to reestablish broken trust and how to rebuild the bond between the parent and the child, rather than just offering suggestions for “a leave plan” [62-65]. Findings in this study showed through the EBPAS questionnaire that professional counselors felt that PCIT could be used to work with women and children living in domestic violent homes [66-68].

Findings from this study support evidence that PCIT could be an effective tool that professional counselors use to address the needs of women and children who live in domestic violence households. In studies examining child abuse, psychologists used PCIT to learn how the bond between a parent and a child is affected when the child is exposed to repeated abuse [69]. What psychologists found through PCIT was parents who abuse their children were often victims of child abuse themselves.